Highlight 17, Enlivening Spaces

Dear Friends,

When I get going too fast at work (every May in fact!), it becomes difficult to keep my desk and the spaces around me tidy. Things piles up faster than I can put them into their place, or create new places for ones that need places. I am aware of an increasing tension when this happens. As some point I find it necessary to take a few hours to bring everything back into order. Everyone has their own relationship to this cycle – some are more able to do it in a regular rhythm – and others whenever it is needed. I was reminded of the dynamics of this recently when studying some material on the nature and life of the elementals in relation to working with my garden.

Linda Thomas, who cleaned the Goetheanum for many years, wrote a lovely article about the spirit of cleaning. It is not just about having neat and clean spaces. The cleanliness and orderliness is important and necessary, but not sufficient for maintaining a living space around us that supports our work in a healthy way. Enlivened space requires awareness and consciousness. read more

A New Image of Waldorf School Organization – M Soule

A new imagination of organizational form and function in a Waldorf school

Summary

After years of working in and with Waldorf schools, I have found that the imaginative thinking about the governance and organizational structure of a school is key to the school having a wholeness. Since each school is independent and unique, and is responsible for creating itself over time, the key to organizational health rests with the capacity of the leadership at any given time to build an imagination of the organization and from this imagination to find insights that can guide thinking about the challenges faced by the school at its unique phase of development. What has developed for me through many conversations is a thinking process that leads to an organic evolving imagination that can fit an organization at any phase of its growth and in any situation.

Starting over

I have been in many schools over the last 20 years and have found that the many attempts to describe the organization using diagrams rarely if ever yields any real insight into the life of the organization and how to manage the operations. With various groups, I have gone through a process of building an imagination of the school which brings new ideas, a new sense of relationship, responsibility and helps identify key areas needing attention.

From the whole to the parts

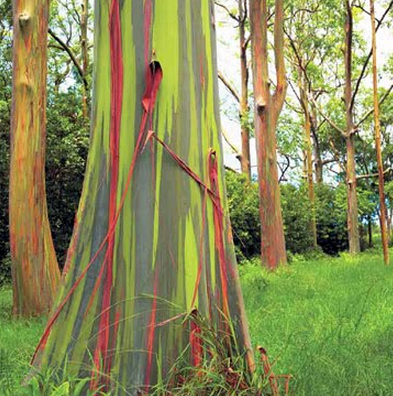

A Waldorf school is a living organization involving many people who each have their own relationship to the endeavor, and who find themselves in groups that have particular roles and responsibilities – all important to the overall function and health of the organism. The school itself is part of its community, an endeavor to create a place where parents can find common ground and inspiration about the care and nurturing of their children. It is also a part of the evolving landscape of the educational community, the non profit community, the philanthropic community and the neighborhood where it resides. As a unique part of the community in which it lives, like any organism in its environment, it needs connection to everything around it for support and nourishment, and some separation from what lives around it for protection and identity.

Like any organism, it has three basic conversations ongoing. First, it has the conversation with itself about its own development – what is its mission, how shall it operate and reflect upon its own life. In this conversation it should be completely free to make its own way, to seek its own light and learn its own lessons. Just like a human being, it is responsible for making its own decisions and judgements and acting accordingly. Secondly it has the conversation with the other institutions and culture around it – how is it connected to other Waldorf shools, to other independent schools, to the government, to its neighbors. In this conversation it should be guided by the agreements it has with others – from being part of the association of Waldorf schools to filing taxes to adhering to fire codes to adhering to state regulations. In this realn it is important that it remembers that it is an equal part of the social fabric and that it has agreements to uphold. Thirdly, the school has a conversation with the earth itself – how it sustains itself, maintains buildings and garners the resources needed to assure its continued existence. This conversation is guided by mutuality – it provides parents with care and nurturing of their children in exchange for financial and personal support, it provides a service to the educational community and receives gifts and resources, it supports many vendors and service providers in exchange for their support.

These three conversations, while essential to any organization, have special significance in a Waldorf school. From the beginning of the first school in 1919, emphasis was placed on the importance of organizing the school from the inside out – that the first conversation, the internal one about its own direction and purpose rooted in self reflection, was the one that should guide the quality of the other conversations, the more outer ones. And this was rooted in the striving of the individuals in the school to be developing themselves. Both the work with the students and the work in organizing the school depend on the inner work of the people involved in the endeavor – their capacity for self reflection. The school was reminded this over and over again – that to be healthy and creative in its task, the individuals must be actively striving towards self-understanding. And this self understanding can come about only when an individual has an active contemplative practice aligned with the impulse of Anthroposophy. But as we know concerning our capacity for nurturing our development, we need help from each other. We are not in a time in history when an individual can develop independently. That means that the work in the school must be guided by processes that allow for individuals to remain independent and free but to seek and explore insights in such a way that their own development is furthered.

From the beginning of Waldorf education and Waldorf schools it has been of the utmost importance for the groups within the school to work within themselves and with each other in ways that seek and explore insights. This requires continual practice. At a simple level this would be expressed at meetings by saying a verse, reading something together, reviewing meetings, having regular meetings between groups and having a clear system of regular conversations between colleagues about their work. But these are just the surface. The work of each group needs to evolve as it seeks both common ground and meaningful ways to support the development of each person in the group. And here is where the faculty as a whole is essential to the work throughout the school. The work of the faculty in meaningful self reflection and the application of insight into the many operations of the school is truly like a heart of the school with the circulation being the sharing of insight as nourishment.

How faculties are prepared and able to do this work is a question. One learns this essential work by doing it, by participating in it. And as the task of holding a class and teaching becomes more and more challenging over time, the amount of energy and time left to spend in deeper work in the faculty as a group is diminished. We are faced with a situation in which there is less time and energy to do deeper work that is essential to the health of the organization. The result is often weakened operations and greater need for outside intervention as the organization is less and less able to meet the demands put upon it. It is a dilemma that when one is ill, one often has the least capacity to heal oneself – too often one must attend to the secondary effects rather than the root cause.

So how does a school potentize its work on seeking the inspired consciousness it needs?

Relationships

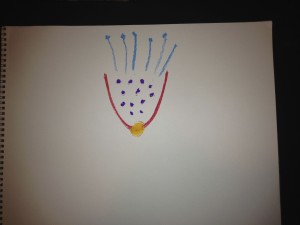

Start with an imagination of a class – we have a teacher dedicated to the growth and development of the students gathered around her. The students (purple) are in the center in the care of the teacher (yellow), surrounded by their parents (light blue) and held in a vessel (red) by the whole faculty and staff.

Fig 1

Fig 1

Now place classes next to each other in a ring. This would create the teachers in a circle with an inner space free from the students and parents surrounded by the classes and parents. What is living between the teachers might be viewed as a kind of sun that radiates out into the classrooms.

Fig 2

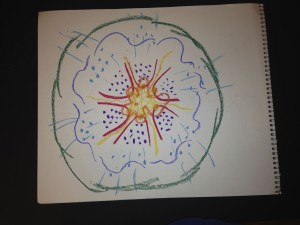

Now we notice that between the classes there are areas that are empty, that we could designate as “the school.” What is it that connects the classes into a whole? In this we could add festivals, assemblies and all activities that involve more than one class.

Fig 3

In this evolved picture one can see the inner realm of the teachers. This space is extremely important to the health of the school. Much has been written about the role of the faculty, the ways the teachers can work together to create harmony and effective working, and the relationship between the faculty and the rest of the organism. In the faculty it is important to note the different task that the class teachers and subject teachers have. One is tasked with guiding the journey of a grou p of students, and the other is tasked with helping all the students make strides in relationship to a subject. How these tow are woven together has a significant effect onteh students and the whole school.

In this picture one can also see that the parents surrounding the classes create a supportive substance around the educational work. In this outer layer, a skin is formed that allows for the organism to have identity and protection. In addition, the skin could be seen as semi permeable and allowing nourishment in and letting out toxins.

Fig 4

Now in the area outside the classes and within the skin we have organs that form to help the overall organism to function. Over time more organs are needed to manage the flow of communication, manage the flow of resources and care for the growing structure of the whole organism. Classes need designated spaces, and structures, and tools that all need to be maintained.

Fig 7

In this figure, we have processes from five realms:

Board processes – like that of skin:

Protection (legal issues)

Nourishment (resources and sustainability)

Identity (mission and vision, evaluation )

Interaction with environment (ambassadorship, community relations)

Sensing imbalance and supporting functions

Administrative processes – like that of internal fluids and organs

Communication

Managing flows of money

Supporting activities of teachers, parents and all organs

Community building in the whole

Faculty Processes – like that of the heart

Tending to students

Collaboration in faculty

Finding inspiration

Being creative

Sensing the whole and the parts

Student Processes – like that of the cells

Playing, working, learning and growing

Parent Processes, like that of the lungs

Caring

Pitching in

Supporting

Reflecting

Connecting and exchanging with the world

In each of these realms, there is a need for an organizing principle or a leading activity.

In the parent realm this can be the class parents in a grade who develop their own structure of support (class rep or class helper) and for the whole parent body it is usually a parent council or parent organization. Its purpose is often to assure that each parent finds their rightful place in the school in which their talents and capacities can best contribute to the whole. It has a second purpose of assuring that the parents as a whole are organized to be best involved in the community building of the school.

In the faculty realm it is two fold : the sections (EC, GS , HS) and the core group, college or leadership team that acts on behalf of the whole.

In the admin realm it is often one or a few administrators tasked with assuring the healthy flow and organization of the administrative realm.

In the board it is the officers and the board development group tasked with helping the board as a whole continue to develop.

In the students it is the classes. In the older sections of the school it can be a student leadership group or council.

Because the organism is an integrated whole, (even thought it might not feel like it at times), every organ (parent council, board, faculty, admin, committees) is connected intimately to the whole and is a microcosm of the whole. Every organ has its own skin, it own identity, its own creativity, its own responsibility for communication etc. all purposefully aligned with the whole organism.

Now we have an overall picture of the organism that can speak to us and with which we can have a conversation.

What happens when a class become weak? What happens when a teacher can’t teach any longer? What happens when the faculty as a group is not able to work toether in such a way as to provide inspiration and insight that can guide the whole organism? Or when they isolate themselves from the rest of the organism and create their own skin that lacks permeability? What dynamic appears when an organization fails to renew its vision? Or when parents who are an integral part of the organism don’t identify with the mission of the school or follow healthy school processes?

Many of the dynamics alive in schools that I have worked with, when seen in the context of a living picture, can be understood more completely and dealt with in relationship to a sense of the whole.

The school is a living organism, that has living processes that function in service to the primary task of the whole – to care for, nurture and guide the development of children who come to the school, to provide support and encouragement to the parents who bring them and to build a conscious community that is committed to the understanding and practice of a new view of what it means to be a realized human being and to be a community.

(Further exploration of the physiology of the organism can be helped by looking at other resources.)

In another article, there is an outline of what aspects of this organism are unique to Waldorf school and what are more general to schools, non profits and businesses. The purpose here is to provide a living picture of a school organism that moves our thinking away from dead diagrams and towards new imaginations and questions.

What I have found important in a picture like this, is that it places the classes and students in the center and the faculty in the center and shows the space required by the faculty from which can radiate the insight needed to sustain the whole organism. This picture allows us to see an image of the healthy social life given to the first school as an imagination for moving forward.

Resources:

Vision in Action: Working with Soul and Spirit in Small Organizations, by Christopher Schaefer and Tino Voors.

Organizational Integrity: How to apply the Wisdom of the Body to Develop Healthy organizations, by Torin Finser.

Where the Spirit Leads – the Evolution of Waldorf School Administration

Social Development Insights of Rudolf Steiner in Waldorf School Administration and the new Leading with Spirit Training program starting this summer.

(In this essay, Michael Soule and his colleagues in the Leading with Spirit training program, discuss the evolution of both the role of the administrator and Rudolf Steiner’s social ideas in Waldorf School’s in the United States over the past 30 years. This article also introduces the people and the ideas behind the new Leading with Spirit administrative training starting this summer sponsored by the Waldorf Institute of SE Michigan, WISM and hosted by Alkion Institute in NY and the Whidbey Island Waldorf School in Washington State.)

In 1986, when I, (Michael Soule) was hired as the administrator of the Seattle Waldorf School, the idea of an administrator in a Waldorf school was still new. Of the few established schools in the Northwest, in Vancouver B.C. and Eugene, OR, there was just one other administrator. I remember the many hours we spent on the phone (yes, long distance) sharing stories and ideas.

What would happen in the 20 years between 1980 and 2000 was akin to a mini educational explosion. In the Northwest region alone, we went from having a single school in Portland, Eugene, Vancouver and Seattle to sprouting 25 new schools – nine within an hour and a half of Seattle. Across the continent, some hundred new schools were founded!

Today a Waldorf school without an administrator is a rarity. The question is: where are these administrators coming from and how do they receive training that will help them succeed in the unique Waldorf organizational culture?

While Waldorf teacher trainings began sprouting up across the country in the ‘80s, there were only two courses that provided professional development for administrative staff until 1993. One was a week-long offering during the spring semester of the Sunbridge year-long teacher training course and the other was a year-long seminar at the Social Development Center at Emerson College. (Both of these programs were developed by Chris Schaefer, a Waldorf graduate, consultant, author and trainer.)

Also in the late ‘80s, a number of leading thinkers in the Waldorf movement gathered regularly at Rudolf Steiner College, in Fair Oaks, CA, to exploring themes of Waldorf school organization, finances, economic life and other social and organizational issues. Participants at these conferences pondered upon what an anthroposophically inspired organization looked like and what were considered the core principles and guiding imaginations that might help a school thrive both as an independent school and as a center of cultural renewal.

I attended a number of these gatherings and the week-long seminar at Sunbridge. Then, after fives years as the Seattle Waldorf School administrator, I took a year off both to travel and to study at the Social Development Center in England. In the following years, I took on the various roles of Waldorf teacher, consultant, AWSNA executive and again a school administrator, but I never lost track of the ideas and questions central to Rudolf Steiner’s insights of how to continually grow an anthroposophically inspired organization. It would be some 20 years before my hopes for a training program for administrators in the Northwest would materialize.

We all know that the hope of Rudolf Steiner, when he helped found the first Waldorf School, was that the school would become a beacon of spiritual impulses for the local community – a center of social/spiritual renewal. This would require a special kind of working together by the teachers and staff and volunteers of the school led by an interest in anthroposophical insights. But who was to lead these endeavors?

It was clear that Steiner imagined that the teachers, trained and experienced, committed to working both educationally and socially out of anthroposophy, would provide leadership to their own schools and that these schools would find support from local groups of people involved in anthroposophy.

What has happened for Waldorf schools in North America is a different story. Today, more than ever, there is a shortage of trained and experienced teachers. The task of teaching has become so demanding that teachers have less and less time to explore the social organizational dimension of the schools. Therefore, to help ease the burden on the teachers, schools have developed professional administrations to share the responsibility of running the schools and instilling related social ideals.

Between 1991 and 2008, Chris Schaefer and a group of colleagues, offered the first training for administrators of Waldorf schools at Sunbridge College in NY. This training arose in response to the problems arising in Waldorf schools related to either hiring administrative staff with no understanding or real connection to the education, or hiring teachers to do administrative work with no professional experience. It was an intensive course that took participants through a journey of exploring the basics of Waldorf education and anthroposophy, helped individuals on their path of self-development and explored the unique organizational dynamics of Waldorf schools.

Much of this curriculum stemmed from Chris Schaefer’s experience as a Waldorf student, as an organizational consultant with various companies and as a teacher at the Social Development Centre at Emerson College, where the focus was on the work of the Dutch anthroposophist and doctor, Bernard Lievegoed. Lievegoed, one of the leading thinkers and practitioners of anthroposhical organizational development in the last century, was a teacher, author, head of the Dutch Anthroposophical Society and a student of Rudolf Steiner’s.

“What we were hoping to do, at the Social Development Centre and at Sunbridge, was to keep the ideas of an anthroposophically inspired organization alive in small groups of people. That’s why each course involved not only helping participants develop their professional organizational skills but helping them each find a living relationship to Steiner's social insights through their own practice of inner work based on anthroposophy. Our hope was to help people become the vessels for new social impulses and to serve and help lead their schools on their individual journey of growth and development. To a great degree we felt successful. One of the challenges we faced was that our students would return to their schools and not have the easiest time integrating their new capacities into the schools’ structures. We spent a lot of time on the phone coaching our students!”

Leading with Spirit picks up where the Sunbridge program developed by Chris Schaefer and his colleagues left off, but with some significant differences. We understand that this type of training program needs to be flexible to meet the many demands of current administrative staff in Waldorf schools. The vision for the program is to offer a regionally based course that can be joined by new students at any point in the program. It will provide students with opportunities and support to do research, to come together in intensive seminars with colleagues, to be able to explore other local and regional weekend offerings, and to provide ongoing mentoring to participants as they meet challenges between courses. All of these are rolled into a flexible but intensive learning journey. (You can find an outline of the course content and process at www.leadingwithspirit.org)

Starting this summer in Hawthorne Valley, NY, hosted by Alkion Teacher Training Center, and by the Whidbey Island Waldorf School in WA, the program begins with one simple week-long intensive. Another program group hosted by the Waldorf Institute of Southern Michigan will start in the summer of 2016 in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The program website provides detailed information.

The future of Waldorf education and the possibility that Waldorf schools can be transformative organizations rests both on the capacity of teachers to continue their good work out of a real creative impulse connected to anthroposophy and the capacity of administrative staff to do the same. Leading with Spirit is one attempt to support this essential task.

A graduate of the first class of the Sunbridge administrative course, Mara White, Director of School and humanities teacher at Waldorf High School of Massachusetts Bay, joined Chris in 1996 as a core faculty member in the Sunbridge administrative course and will again be instrumental in the program being launched this year. Working with Bob Dandrew, the Chair and Development Director of AWSNA in 1993, Mara helped establish a network of administrative and development staff in Waldorf schools across the continent to grow a supportive community of those working in schools in administrative capacities. The goal was to highlight the importance of administrative work and to encourage an understanding that this work in the schools is, as with teaching, a vocation.

What grew from these efforts was named DANA (Development and Administrative Network of AWSNA). DANA is still active today, with coordinators in each of AWSNA’s eight regions. “DANA was another hope to provide individuals who were involved in school administration with support, collegial mentoring and shared resources and to gather information for the movement’s leaders on the needs of the administrative work and staff in our schools. The DANA network initiated an effective practices project (resources on the AWSNA website), hosted conferences and worked to be active as the administrations in schools grew more and more professional and better rooted in anthroposophical principles. After many years of work with DANA, I am even more committed to providing professional level training focused for administrative staff in Waldorf schools. We need a training that can be flexible, and both regional and continental, at the same time. Our new work with Leading with Spirit is an attempt to do this.”

Another collaborator on Leading with Spirit, Marti Stewart, began her administrative work at City of Lakes Waldorf School thirteen years ago. Marti views her work as an Administrative Director as a true vocation and believes in the profound importance of administrative work in creating and maintaining health in our schools. "In the same way as the teacher guards and respects the unique gifts each child brings to the class community, it is the task of the administrative staff to honor and nurture the gifts of everyone in the adult community." Marti participated in the administrative course at Sunbridge and was inspired to look at the deeper aspects of guiding the administrative work in a Waldorf School. Now, as a regional DANA Coordinator in the Great Lakes Region, she is excited to be a part of an administrative course that can support individuals who are serving in administrative roles across the continent. "I am especially excited that the Waldorf Institute of Southern Michigan (WISM) is willing to offer the training program in our region."

Sian Owen-Cruise agrees. As High school Coordinator at the Rudolf Steiner School of Ann Arbor and Interim Director at the Waldorf Institute of Southeastern Michigan, Sian is another colleague in the movement who started her work in administration and sees clearly that the development of Anthroposophically centered administrative structures is essential to the growth and development of Waldorf education in North America. Sian comments “it is clear to me that my path in Waldorf Education is one of administration and the building of collaborative schools that truly support children and their families, and have an impact on the wider community they are part of.” Sian is also a graduate of the Sunbridge course.

In Steiner’s life, after many initiatives were launched in 1917 around his social ideals, he found that people did not have the capacities to be successful in some degree because they were not prepared to understand the spiritual ideals needed to be creative in new ways. While this realization was a life disappointment for Steiner it also served as one of the impulses for Waldorf education. Steiner believed that a new educational process, and a journey based on a new understanding of the human being, might have the hope of preparing generations of young souls to meet the social challenges of their times with new capacities. That is still our hope with Waldorf Education. And that is the basis for this new training program.

Come join us this summer.

Management and Governance – Dianna Bell

Management vs Governance – It’s Not That Easy

WRITTEN BY DIANNE BALL - NOVEMBER 3, 2010

Estimated read time: 4 minutes

( Editor note: This article describes the three possible modes of board work in an organization. It assumes the role of CEO and a hierarchical structure that are not common in Waldorf schools. But the concept of the different modes of action of a board still hold , even in our collaborative organizations. You need to do a bit of translating to make it relevant to our situations. Still I have worked with different schools where boards worked in these modes and each mode has specific strengths and weaknesses. There is a lot of interest in schools for developing boards that are more strategic than managing, but the lack of resources and the infancy of many administrative structures often makes a board feel they are responsible for cleaning things up and they feel justified in being strongly managerial. An experienced administrator, a strong administration or a well functioning college of teachers all contribute to allowing a board to be more involved in being a watchdog than a pilot. -ms-)

During our education on governance and directorship we are taught that “directors govern and managers manage”. The analogy of steering versus rowing is often used to describe the delineation of roles between directors and managers. Most directors are well aware of this.

It seems that many boards are challenged with the task of getting the ‘right’ balance between governance and management. Why is this so? Experienced directors are aware that every board is different in terms of the way they implement their governance role. Lack of clarity and agreement about this issue can be a source of misunderstanding and potential conflict around the board table.

According to Demb and Neubauer (1992)* there are three main archetypal ways for boards to implement their governance role; named the watchdog, the trustee and the pilot mode. In summary, a ‘watchdog’ role is one in which the board provides total oversight and has no direct involvement in the company’s activities. The ‘trustee’ role is where the board behaves like a guardian of assets and is accountable to shareholders and society for those assets. In a ‘pilot’ role the board takes an active role in directing the business of the corporation.

There is no ‘right’ approach for a board to take. The stance taken by a board depends on the company’s growth and development, the nature of the industry, national legal requirements and culture and preference. To illustrate how these modes operate we use an example of how the board of Company X would address issues of workplace safety in an industry where safety was a major risk.

In the watchdog mode the board monitors the process of corporate activity. It is not necessarily a passive role. If Company X performed in this way they could take an active role in setting up mechanisms of safety and security as an issue of high risk and concern, and scrutinise in detail. The difference between an active watchdog role and a passive role would be the degree of scrutiny and interrogation of information that occurs. The focus of a board in watchdog mode is on monitoring and evaluation and confirming decisions made by the CEO.

This mode could be effective if all of the following conditions are met:

- Directors are satisfied that appropriate systems and policies are in place and have been demonstrated to be effective. The important point is demonstration or evidence of effectiveness rather than just the assurance of the CEO.

- Directors are satisfied that information reported by the CEO includes relevant indicators and other information that directly reflects the integrity of safety and security systems.

- The CEO is willing and able to guarantee that appropriate safety systems are in place and they have been tested and found to be robust.

- Contingency and business continuity plans are regularly reviewed and tested and the results reported to the board.

- Directors are able to exercise critical and independent judgment.

If the board of Company X was in trustee role it would ensure that activities enhance corporate value; that is, ensuring that assets used in the business such as natural assets, human, finance, reputation and others, would at the least avoid being depleted. The board would be involved in evaluating what the company defines as its business as well as how that business is conducted.

If Company X was in trustee mode it would be more actively involved than a watchdog board but still confirming management decisions. This involvement would be limited in the initiation and implementation of safety systems but substantially involved in analyzing options, monitoring and evaluating results. The following actions would be undertaken in this mode:

- With input from the CEO the board would give direction to senior management to develop an appropriate safety and risk management system. The board would set the parameters and expectations and allow senior management to develop the detail.

- Directors would be actively involved in analysing options in the safety strategy.

- The CEO would implement the safety systems and the board would be intimately involved in monitoring progress and evaluating the results.

The trustee mode would give sufficient attention to the integrity of safety systems, regardless of whether the existing safety systems are appropriate or otherwise.

So how does this compare with the pilot mode? As the name suggests, in pilot mode the board would be actively involved in the direction, management, implementation and evaluation of safety systems. The board would be making more decisions than in the other modes such as the following:

- Deciding what constitutes a safety system and what is to be installed;

- Determining the degree and method of integrating systems with customers;

- Actively analysing options;

- Deciding how and when to implement changes to the safety system;

- Detailed monitoring of the safety systems, even when there is no evidence of problems;

- Close scrutiny and evaluation of the systems.

Pilot mode could be appropriate in situations where there was evidence of significant issues or after a safety issue had occurred and the board felt the need to directly intervene. Pilot mode would be more time consuming and involve greater degree of involvement by directors.

We can see from the above examples that a board can fulfil its governance role and be involved in decision making in a range of different ways, all of which are appropriate in the right circumstances.

It is important for boards to take a step back and reflect on the way they behave and ask whether the degree of involvement by directors is appropriate for this organisation, at this time, in this context. Whether the issue is explored in a board evaluation process or discussed around the table, it is important that all directors give consideration as to what is appropriate for your organisation and be in agreement about what is required. Maybe, just maybe, it is time to do things a little differently.

About Dianne Ball

Dianne has thirty years experience working in service organisations, mainly in the public and private health sectors and consulting with PriceWaterhouseCoopers. Her roles include senior management and executive positions including CEO Australian College of Health Service Executives, and General Manager Operations with McKesson Asia Pacific. She has several years experience as a non executive director and has Chaired board committees and working parties. Dianne’s particular work interests lie in organisational change, corporate governance, risk and strategy.

Good Governance Checklist from CWP

GOOD GOVERNANCE: THE ESSENTIAL CHECKLIST

Based on and adapted from Capacity Waterloo Region on the internet

Editor's note (I especially like this checklist more than others because it emphasizes attention to overlaps that normally cause problems in Waldorf schools. You can certainly adapt it for your use. As with all checklists, it is a good place to launch a discussion of roles, responsibilities and agreements. -ms-)

CO M M UN I CA T I O N

The Board speaks collectively with One Voice at all times

Admin/Faculty reports to the Board on a regular basis

The Admin/Facultyalways keeps the Board informed of major internal / external issues or trends

The Admin/Faculty does not instruct any Board member, including the Chair of the Board

The Board makes an honest effort to engage with the membership

The Admin/Faculty makes an honest effort to engage with the beneficiaries & customers

RO L E S A N D RE S P O N S I B I LI T I E S

The Board focuses on governance duties, i.e., strategic visioning & long-term planning

The Admin/Faculty focuses on operational duties, i.e., annual budgeting, goal setting, day-to-day

The Board does not instruct the Executive Director or staff on day-to-day duties

The Admin/Faculty does not instruct any Board member, including the Board Chair

The Board Chair facilitates free and open meeting discussions based on a set agenda

MON I T OR I N G

Detailed minutes are kept from all Board meetings, i.e., Motions, Vote Counts, etc.

The Board monitors its own performance on a regular basis, e.g., Self-Evaluations

The Board evaluates the Administrator’s fulfillment of strategic objectives

The Board monitors the organization’s financial conditions on a quarterly basis

Audited financial statements are readily available and accessible to the membership

CO M M I T T E E W O RK

Board committees have a set mandate, membership, and lifespan

Board committees report to the Board and thus have no binding authority

Board and staff committees do not have overlapping mandates

Board members on staff committees do not direct staff or report content to the Board

Board committees are used infrequently, as boardroom discussion is paramount

AC C O U NT AB I L I T Y

The Mission, Vision, and Values are drafted and enforced by the Board

The Admin/Faculty is fully accountable to the Board for all activities & actions of the organization

The Board remains accountable to the membership at all times

Confidentiality is respected by all Board members and staff alike

The Board is ethical, prudent and legal in all of its duties

Policy Governance Introduction by John and Miriam Carver

Carver's Policy Governance® Model in Nonprofit Organizations

by John Carver and Miriam Carver

Over the last decade or two, there has been increasing interest in the composition, conduct, and decision-making of nonprofit governing boards. The board-staff relationship has been at the center of the discussion, but trustee characteristics, board role in planning and evaluation, committee involvement, fiduciary responsibility, legal liability, and other topics have received their share of attention. Nonprofit boards are not alone, for spirited debate about the nature of business boards has been growing as well. Whatever the reasons for this intense interest in governance, the Policy Governance model for board leadership, created by the senior author, is frequently a primary focus of debate.

The Nature of Governance and the Need for Theory

The Policy Governance model is, at the same time, the most well-known modern theory of governance worldwide and in many cases the least understood. It applies to governing boards of all types—nonprofit, governmental, and business—and in all settings, for it is assembled from universal principles of governance. In this article, we will focus exclusively on its use in nonprofit boards, though many descriptions of its application in business (for example, Carver, 2000a, 2000c) and government (for example, Carver, 1996a, 1997d, 2000b, 2001; Carver and Oliver, 2002) are available elsewhere.

Governing boards have been known in one form or another for centuries. Yet throughout those many years there has been a baffling failure to develop a coherent or universally applicable understanding of just what a board is for. While comparatively little thought has been given to developing governance theory and models, we have seenmanagement of nonprofit organizations transform itself over and over again. Managers have moved through PERT, CPM, MBO, TQM, and many more approaches in a continual effort to improve effectiveness. Embarrassingly, however, boards do largely what they have always done.

We do not intend to demean the intent, energy, and commitment of board members. There are today many large and well known organizations that exist only because a dedicated group of activists served as both board and staff when the organization was a "kitchen table" enterprise. Board members are usually intelligent and experienced persons as individuals. Yet boards, as groups, are mediocre. "Effective governance by a board of trustees is a relatively rare and unnatural act . . . . trustees are often little more than high-powered, well-intentioned people engaged in low-level activities" (Chait, Holland, and Taylor, 1996, p. 1). "There is one thing all boards have in common . . . . They do not function" (Drucker, 1974, p. 628). "Ninety-five percent (of boards) are not fully doing what they are legally, morally, and ethically supposed to do" (Geneen, 1984, p.28). "Boards have been largely irrelevant throughout most of the twentieth century" (Gillies, 1992, p. 3). Boards tend to be, in fact, incompetent groups of competent individuals.

An extraterrestrial observer of board behavior could be forgiven for concluding that boards exist for several questionable reasons. They seem to exist to help the staff, to lend their prestige to organizations, to rubber stamp management desires, to give board members an opportunity to be unappointed department heads, to be sure staffs get the funds they want, to micromanage organizations, to protect lower staff from management, and sometimes even to gain some advantage for board members as special customers of their organizations, or to give board members a prestigious addition to their resumes.

But these observations—accurate though they frequently are—simply underscore the disclarity of the board's rightful job. Despite the confusion of past and current board practices, we begin in this article with the assertion that there is one central reason to have a board: Simply put, the board exists (usually on someone else's behalf) to be accountable that its organization works. The board is where all authority resides until some is given away (delegated) to others. This simple total authority-total accountability (within the law or other external authorities) is true of all boards that truly have governing authority.

The Policy Governance model begins with this assertion, then proceeds to develop other universally applicable principles. The model does not propose a particular structure. A board's composition, history, and peculiar circumstances will dictate different structural arrangements even when using the same principles. Policy Governance is a system of such principles, designed to be internally consistent, externally applicable, and—to the great relief of those concerned with governance integrity—logical. Logical and consistent principles demand major changes in governance as we know it, because these principles are applied to subject matter that has for many years been characterized by a hodgepodge of practices, whims of individuals, and capricious decision making.

Such a change is a paradigm shift, not merely a set of incremental improvements to the status quo. Paradigm shifts are difficult to cope with, since they often render previous experience unhelpful; they demand a significant level of discipline to be put into effect. But if there is sufficient discipline to use the Policy Governance model in its entirety, board leadership and the accountability of organizations can be transformed.

It is important that we underscore this point. Using parts of a system can result in inadequate or even undesirable performance. It is rather like removing a few components from a watch, yet expecting it still to keep accurate time. Unlike the traditional practices to which boards have become accustomed, the Policy Governance model introduces an integrated system of governance (Carver and Carver, 1996; Carver, 1997).

Greater effectiveness in the governing role requires board members first to understand governance in a new way, then to be disciplined enough to behave in a new way. Boards cannot excel if they maintain only the discipline of the past any more than managers of this new century can excel if they are only as competent as those of the past. Does this ask too much of boards? Perhaps it does ask too much of many of today's board members. Yet there are other board members—or potential board members who thus far have refused to engage in either the rubber-stamping or the micromanaging they see on boards—who would rejoice in greater board discipline.

The Policy Governance model requires that boards become far more enlightened and more competent as groups than they have been. If that means losing some board members as the composition of boards goes through change, then the world will be the better for it. The Policy Governance model is not designed to please today's board members or today's managers. It is designed to give organizations' true owners competent servant-leaders to govern on their behalf.

Board as Owner-Representative and Servant-Leader

In the business sector, we can easily see that a board of directors is the voice of the owners (shareholders) of the corporation. It is not always apparent that nonprofit organizations also have owners. Certain nonprofits, such as trade associations or professional societies, are clearly owned by their members. Beyond such obvious cases of ownership, however, it is useful to conceive that community-based agencies in the social services, health, education, and other fields are "owned" by their communities. In neither trade associations nor community agencies is there is a legal equivalent of shareholders, but there is a moral equivalent that we will refer to as the "ownership." Looking at ownership in this very basic way, it is hard to conceive of any organization that isn't owned by someone or some population, at least in this moral sense.

The Policy Governance model conceives of the governing board as being the on-site voice of that ownership. Just as the corporate board exists to speak for the shareholders, the nonprofit board exists to represent and to speak for the interests of the owners.

A board that is committed to representing the interests of the owners will not allow itself to make decisions based on the best interests of those who are not the owners. Hence, boards with a sense of their legitimate ownership relationship can no longer act as if their job is to represent staff, or other agencies, or even today's consumers (we will use that word to describe clients, students, patients, or any group to be impacted). It possible that these groups are not part of the ownership at all, but if they are, it is very likely they constitute only a small percentage of the total ownership.

We are not saying that current consumers are unimportant, nor that staff are unimportant. They are critically important, just as suppliers, customers, and personnel are for a business. It is simply that those roles do not qualify them as owners. They are due their appropriate treatment. To help in their service to the ownership, Policy Governance boards must learn to distinguish between owners and customers, for the interests of each are different. It is on behalf of owners that the board chooses what groups will be the customers of the future. The responsible board does not make that choice on behalf of staff, today's customers, or even its own special interests.

Who are the owners of a nonprofit organization? For a membership organization, its members are the owners. For an advocacy organization, persons of similar political, religious, or philosophical conviction are the owners. There are many variations. But for purposes of this paper, we will assume a community organization, such as a hospital, mental health or family service agency, for which we can confidently say that the community as a whole is the legitimate ownership. In this case, it is clear that in a community organization, the board must be in a position to understand the various views held in the community about the purpose of the organization. In short, if the community owns the organization, what does the community want the organization for?

Traditionally, boards have developed their relationships largely inside the organization—that is, with staff. Policy Governance demands that boards' primary relationships be outside the organization—that is, with owners. This parallels the concept of servant leadership developed by Greenleaf (1977, 1991), in that the board is first servant, before it is leader. It must lead the organization subject to its discoveries about and judgments of the values of the ownership.

We have thus far referred repeatedly to the board and very little to board members; that is intentional. Since we are now establishing the starting point for governance thinking, it is important that we start with the body charged with authority and accountability—the board as a group, not individual board members. It is the board as a body that speaks for the ownership, not each board member except as he or she contributes to the final board product. So while we might derive roles and responsibilities for individual board members, we must derive them from the roles and responsibilities of the board as a group, not the other way around. Hence, board practices must recognize that it is the board, not board members, who have authority.

The board speaks authoritatively when it passes an official motion at a properly constituted meeting. Statements by board members have no authority. In other words, the board speaks with one voice or not at all. The "one voice" principle makes it possible to know what the board has said, and what it has not said. This is important when the board gives instructions to one or more subordinates. "One voice" does not require unanimous votes. But it does require all board members, even those who lost the vote, to respect the decision that was made. Board decisions can be changed by the board, but never by board members.

The Necessity for Systematic Delegation

On behalf of the ownership, the board has total authority over the organization and total accountability for the organization. But the board is almost always forced to rely on others to carry out the work, that is, to exercise most of the authority and to fulfill most of the accountability. This dependence on others requires the board to give careful attention to the principles of sound delegation.

Since the board is accountable that the organization works, and since the actual running of the organization is substantially in the hands of management, then it is important to the board that management be successful. The board must therefore increase the likelihood that management will be successful, while making it possible to recognize whether or not it really is successful. This calls upon the board to be very clear about its expectations, to personalize the assignment of those expectations, and then to check whether the expectations have been met. Only in this way is everyone concerned clear about what constitutes success and who has what role in achieving it.

At this point, we wish to introduce the chief executive (CEO) role. (Policy Governance works in the absence of a CEO role, but the governing job is more difficult than with a CEO.) We are not concerned whether the CEO is called executive director, director-general, president, general manager, superintendent, or any other title. We are, however, concerned how the role is defined and we will use the term "CEO" to reflect the role definition we recommend.

We recommend that the board use a single point of delegation and hold this position accountable for meeting all the board's expectations for organizational performance. Naturally, it is essential that the board delegate to this position all the authority that such extensive accountability deserves. The use of a CEO position considerably simplifies the board's job. Using a CEO, the board can express its expectations for the entire organization without having to work out any of the internal, often complex, divisions of labor. Therefore, all the authority granted by the board to the organization is actually granted personally to the CEO. All the accountability of the organization to meet board expectations is charged personally to the CEO. The board, in effect, has one employee.

It is important that boards maintain a sense of cause and effect with respect to their CEOs. The board creates the CEO; the CEO does not create the board. As the board contemplates its accountability to the ownership, it decides that creating a CEO role will be a key method in fulfilling that accountability. It is true that a founding father or mother will sometimes be the inspiration for a new organization, so that the board then created occurs after rather than before the founder. If the founder becomes the new CEO, it will seem that the CEO is parent to the board. Boards established in this way make a grave error when they mistake an accident of history for a proper view of their accountability. The CEO role, as such, is even in these cases created and governed by the board (see Carver, 1992).

Consequently, in every case, the board is totally accountable for the organization and has, therefore, total authority over it—including over the CEO. We can say that the board is accountable for what the CEO's job is and that the CEO do the job well. But we cannot say the CEO is accountable for what the board's job is and that the board do its job well. Unfortunately, much of current nonprofit practice supports this board-staff inversion. CEOs are expected to tell their boards what to talk about (provide agendas), to pull their boards together when there is dissension, and to orient new board members to their job. Nowhere else in an organization are subordinates responsible for the conduct of the superiors. Yet virtually all nonprofit literature on governance falls into this fallacy of CEO-centrism. "Thus, we argue, the board's performance becomes the executive's responsibility," say Herman and Heimovics (1991, p. xiii), a position we contend excuses and prolongs board irresponsibility.

We have said being accountable in leadership of the organization requires the board (1) to be definite about its performance expectations, (2) to assign these expectations clearly, and then (3) to check to see that the expectations are being met. Traditional governance practices lead boards to fail in most or all of these three key steps.

Board expectations—which are instructions—when they are stated at all, tend to be unclear, incomplete, or a mixture of whole board and individual board member expressions. Board members form judgments of staff performance on criteria the board (as a whole body) has never stated. Regular financial reports report against few or no criteria. Staff members can be seen taking notes of what individual board members say, as if it matters and as if they work for the board members rather than the CEO. Boards decide whether CEO's budgets merit approval when they have never stated the grounds for approval and disapproval. Virtually every board meeting—other than in Policy Governance boards—is testimony to carelessness of delegation and role clarity.

Traditional governance allows boards to instruct staff by the act of approving staff plans, such as budgets and program designs. When the board has approved a staff recommendation, doesn't the resulting approved document become a clear board instruction? Actually, it does not. For example, when a board approves the CEO's personnel policies or budget, does it really mean as an instruction every tiny segment of that document? Does every budget line and the smallest issues of a program plan become a criterion on which the CEO will be judged? Certainly not. Even the most micromanaging board does not go that far. But to what level of detail should the CEO treat the approved document as being a board instruction, therefore a criterion for evaluation? The tradition-blessed habit of board approvals is a poor substitute for setting criteria, then checking that they have been met. Board approvals are not proper governance, but commonplace examples of boards not doing their jobs.

What about the clear assignment of expectations to a person or persons? In conventional practice, boards' delegation to a CEO is frequently compromised by delegating the same responsibilities more than once or by delegating to around the CEO to sub-CEO staff. An example of the former is when a board charges the CEO and a board finance committee for financial decisions. Delegating around the CEO occurs either when a board gives instructions to the financial officer or other person who reports to the CEO or when a board itself judges the performance of sub-CEO staff.

Finally, in the absence of clear instructions or clear assignment, evaluating performance is an exercise in futility. Yet boards receive volumes of information that purports to monitor organizational performance. The sheer amount of information masks the fact that proper monitoring is still not occurring. Because monitoring performance is the systematic disclosure of whether board expectations have been met, monitoring that is fair and incisive can only occur after clearly stated and clearly assigned board expectations.

Using the Ends/Means Distinction

The point was made earlier in this paper that the board is accountable that the organization works. Clearly, the word "works" must be defined; defining it establishes the board's expectations for the organizations, the performance that will constitute success. The board need not control everything, but it must control the definition of success. It is possible to control too much, just as it is possible to control too little. It is possible to think you are in control when you are not. The zeal of a conscientious board can lead to micromanagement. The confidence of a trusting board can lead to rubber stamping. Defining success is a matter of controlling for success, not for everything. How can a board control all it must, rather than all it can?

Boards have had a very hard time knowing what to control and how to control it. Policy Governance provides a key conceptual distinction that enables the board to resolve this quandary. The task is to demand organizational achievement in a way that empowers the staff, leaving to their creativity and innovation as much latitude as possible. This is a question of what and how to control, but it is equally a question of how much authority can be safely given away. We argue that the best guide for the board is to give away as much as possible, short of jeopardizing its own accountability for the total.

What is there to control? In any organization, there are uncountable numbers of issues, practices, and circumstances being decided daily by someone. The Policy Governance model posits that all of these decisions can be classified as those that define organizational purpose, and those that don't. But the model calls for a very narrow and careful definition of purpose: it consists of what (1) results for which (2) recipients at what (3) worth.

Let us define these more fully: Some decisions directly describe the intended consumer results of the organization, for example, reading skills, family harmony, knowledge, or shelter from the elements. Some decisions directly describe the intended recipients of such results, such as adolescents, persons with severe burns, or low income families. Some describe the worth of the intended results, such as in dollar cost or priority against other results.

In Policy Governance, this triad of decisions is called "ends." Ends are always about the changes for persons to be made outside the organization, along with their cost or priority. Ends never describe the organization itself or its activities. For example, the professional and technical activities in which the organization engages are not ends. In a school, for example, which students should acquire what knowledge at what cost are ends issues. Ends are about the organization's impact on the world (much like cost-benefit) that justify its existence.

Any decision that is not an ends decision is a "means" decision. In that same school, the choice of reading program, teachers' credentials, and classroom arrangement are means issues. Most decisions in an organization are means decisions; some are very important means. But even if a decision is extremely important, even if it is required by law, even if it is critical to survival, unless it passes the ends test (designation of consumer results, which consumers, or the worth of consumer results), it is not an ends decision. Hence, means include personnel matters, financial planning, purchasing, programs, services and curricula, and even governance itself. No organization was ever formed so it could be well governed, have good personnel policies, a fine budget, sound purchasing practices, or even nicely planned services, programs or curricula.

The ends/means distinction is critical. Many boards claiming to use the model routinely confuse the Policy Governance meaning of ends and means, thereby sacrificing much of the benefit the model can give. For example, means is not synonymous with "administration" as some have misinterpreted (Herman and Heimovics, 1991, p. 44). Ends is not synonymous with "strategic plan," as others have misinterpreted (Murray, 1994). The ends/means distinction is not comparable to any other distinction used in management or governance; it is not parallel to policies/procedures, strategies/tactics, policy/administration, or goals/objectives. Indeed, ends may include very small and specific decisions about a single consumer, while means may include very important programmatic decisions as well as how a board constructs its committees. The ends/means distinction is exclusively peculiar to Policy Governance (with the possible exception of Argenti, 1993) and, therefore, is governed by Policy Governance principles. In Policy Governance,means are means simply because they are not ends.

Are ends the same as mission? Unfortunately, the answer is usually "no," because mission statements have not traditionally had to conform to the definition we have given ends. Consider the following mission statement of a mental health center: "The mission of the XYZ Center is to be a responsible employer, providing quality mental health services in a cost-efficient manner." This statement—quite acceptable in traditional governance—is entirely means, no ends. This organization can fulfill its mission even if consumers' lives are not any better. In contrast, consider this broad statement of ends: "The XYZ Center exists so that people with major mental illness live productive lives in an accepting community at a cost comparable to other providers." In the latter, unless the targeted group are benefited in the required way, the organization is not successful, no matter how good an employer it is and no matter how much "quality" its services have. Notice that the cost component in the first statement is the cost of staff activity (services), while in the second statement it is the cost of consumer results.

No matter how central ends are to the organization's existence, however, because the board is accountable for everything, it is accountable for means as well. Accordingly, it must exercise control over both ends and means, so having the ends/means distinction does not in itself relieve boards from any responsibility. The ends/means distinction does, however, make possible two entirely different ways of exercising control, ways that—taken together—allow the board to have its arms responsibly around the organization without its fingers irresponsibly in it, ways that for the staff maximize accountability and freedom simultaneously. The board simply makes decisions about ends and means—that is, it controls the organization's ends and means—in different ways, as follows:

- Using input from the owners, staff, experts and anyone in a position to increase the board's wisdom, the board makes ends decisions in a proactive, positive, prescriptive way. We will call the board documents thus produced "Ends policies."

- Using input from whoever can increase board wisdom about governance, servant leadership, visioning, or other skills of governance and delegation, the board makes means decision about its own job in a proactive, positive, prescriptive way. We will call the board documents thus produced "Governance Process policies" (about the board's own job) and "Board-Staff Linkage policies" (about the relationship between governance and management). Both of these categories are means, but they concern means of the board, not the staff.

- Using input from whoever can increase its sense of what can jeopardize the prudent and ethical conduct of the organization, the board makes decisions about the staff's means in a proactive, but negative and boundary-setting way. Because these policies set forth the limits of acceptable staff behavior, that is, the unacceptable means, we will call the board documents thus produced "Executive Limitations policies."

At this point in our argument, we have used the ends/means concept to introduce new categories of board policies. These categories of board policies are exhaustive, that is, no other board documents are needed to govern except bylaws. (Articles of incorporation or letters patent are required to establish the nonprofit as a legal entity, but these are documents of the government, not the board.) We will not discuss bylaws here, except to say they are necessary to place real human beings (board members) into a hollow legal concept (the corporate "artificial person") (Carver, 1995). However, so that we might continue to discuss the concepts represented by the words "ends" and "means," yet distinguish the titles of policy categories, we will capitalize Ends, Executive Limitations, Governance Process, and Board-Staff Linkage.

The negative policies about operational means requires further discussion. Here is the logic: If the board has established Ends and has determined through monitoring that those Ends are actually accomplished, it can be argued that the staff means must have worked. In other words, the means by which Ends were accomplished, though interesting, is of little importance to the board. This logic is largely accurate, but there is an important problem with it. Some means can be unacceptable even if they do work. Means that are effective, but still "unacceptable" are ones that are improper treatment of people or assets, that is, means that are imprudent or unethical. Consequently, although there is no reason for a board to control staff means decisions for reasons of effectiveness, there is reason to control staff means for reasons of prudence and ethics.

Whoever is directly responsible for producing ends must decide which means to use. That is, one must be prescriptive about one's own means. But the board is not charged with producing ends, only with defining them. It is to the board's advantage to allow the staff maximum range of decision-making about means, for skill to do so is exactly why staff were employed. If the board determines the means of its staff, it can no longer hold the staff fully accountable for whether ends are achieved, it will not take advantage of the range of staff skills, and it will make its own job more difficult. Happily, it is not necessary for the board to tell the staff what means to use. In Policy Governance the board tells the staff or—more accurately—the CEO what means not to use!

Therefore, it is the board's job to examine its values to determine those means which it does not want in its organization, then to name them. The board can then tell its CEO that as long as the Ends are accomplished and the unacceptable means do not occur, the CEO can make all further decisions in the organization that he or she deems wise. It is in this way that extensive, albeit explicitly circumscribed, authority is granted to the CEO. Effectiveness demands a strong CEO; prudence and accountability to the board demand that the CEO's power be bounded.

This unique delegation technique has a number of advantages. First, it recognizes that board interference in operational means makes ends harder and more expensive to produce. Therefore, delegation which minimizes such interference is in the board's interest. Second, it accords to the CEO as much authority as the board can responsibly grant. Therefore, there is maximum empowerment inside the organization to harness for ends achievement. Third, it gives room for managerial flexibility, creativity and timeliness. Therefore, the organization can be agile, able to respond quickly to emergent opportunities or threats. Fourth, it dispels the assumption that the board knows better than the staff what means to use. Therefore, the board does not have to choose between overwork and being amateurs supervising professionals. Fifth, in this system all means that are not prohibited are, in effect, pre-approved. Therefore, the board is relieved from meticulous and repetitive approval of staff plans. Sixth, and perhaps most importantly, by staying out of means decisions, except to prohibit unacceptable means, the board retains its ability to hold the CEO accountable for the decisions that take place in the system.

Thus, when we say a board is responsible that its organization works, we simply mean that the organization (1) accomplishes the intended results for the intended people at the intended cost or priority—expressed in the board's Ends policies; and that it (2) avoids unacceptable methods, conduct, activities, and circumstances—unacceptable means expressed in the board's Executive Limitations policies.

Expressing Expectations in Nested Sets

We have established that Policy Governance boards express their expectations for themselves and for their organizations in four categories of board policies: Ends, Executive Limitations (the unacceptable means), Governance Process, and Board-Staff Linkage (the latter two are board means divided into two parts). The separation of organizational values into these categories is a major organizing principle for governing boards. These four categories completely embrace all possible organizational values (except those more pertinent to articles of incorporation/letters patent and bylaws)—no other policies or documents are needed. But another feature must be added to enable the board to address its desired level of specificity within these categories.

To ensure precision as well as completeness in policy-making, Policy Governance provides an additional principle, one which recognizes the varying sizes of issues and values. One Ends statement of a nonprofit board may be that persons without shelter should have adequate housing. Another may be that families with school age children should have housing that allows children of different genders to sleep in separate rooms. It is easy to see that the second example is more detailed, or "narrower," than the first. Notice that these two statements can be pictured as a set of nested bowls, in that the first is a broader value that includes the second one within it. Even more detailed choices exist within the second level, and so on to third, fourth, and more bowls until the specificity reaches a level where Mr. Smith rather than Mr. Jones gets a particular amount of shelter next week.

Now let's illustrate the "nested bowls" concept with an example of unacceptable means. One means value of a nonprofit board may be that the CEO not allow anything imprudent, illegal or unethical. Another may be that unbonded persons may not have access to material amounts of funds. The first example is a broader prohibition than the second, but less specific. Even more detailed "bowls" exist, of course, such as a further proscription against access to more than $5,000 on any one occasion or more than $8,000 cumulatively over a one year period.

Board values about ends and unacceptable means, as well as the board's own means, then, can be stated broadly, or more narrowly. The advantage of stating values broadly is that such a statement is inclusive of all smaller statements. The disadvantage, of course, is that the broader the statement, the greater is the range of interpretation that can be given to it. To take advantage of the fact that values or choices of any sort can be seen as nested sets, the Policy Governance board begins its policy making in all four categories by making the broadest, most inclusive statement first.

The board then considers the range of interpretation that such a statement allows, and determines whether it is comfortable with the statement being given any interpretation that is reasonable. If the board would be uncomfortable delegating such a range, that is a signal that the board must define its words more narrowly, moving into more detail one level at a time. At some point, the board will have narrowed its words to the point that it can accept any reasonable interpretation of those words. Now the board has reached the point of delegation.

As an example, consider an Executive Limitations policy in which the board is putting certain financial conditions and activities "off limits." At the broadest level, the board might say: "With respect to actual, ongoing financial condition and activities, the CEO shall not allow the development of fiscal jeopardy or a material deviation of actual expenditures from board priorities established in Ends policies." That covers the board's concerns about the organization's current financial condition at any one time, for there is likely nothing else to worry about that isn't included within this "large bowl" proscription.

However, most boards would think such a broad statement leaves more to CEO interpretation—even if reasonable interpretation—than the board wishes to delegate. Hence, the board might add further details, such as saying the CEO shall not: (1) Expend more funds than have been received in the fiscal year to date except through acceptable debt. (2) Indebt the organization in an amount greater than can be repaid by certain, otherwise unencumbered revenues within 60 days, but in no event more than $200,000. (3) Use any of the long term reserves. (4) Conduct interfund shifting in amounts greater than can be restored to a condition of discrete fund balances by unencumbered revenues within 30 days. (5) Fail to settle payroll and debts in a timely manner. (6) Allow tax payments or other government ordered payments or filings to be overdue or inaccurately filed. (7) Make a single purchase or commitment of greater than $100,000, with no splitting of orders to avoid this limit. (8) Acquire, encumber or dispose of real property. And (9) Fail to aggressively pursue receivables after a reasonable grace period.

A given board might go into less or more detail than in this example. But in any case, these principles stay intact: The language moves from a broad level toward a lesser level (we showed two levels in the example just given). The values that become policy are generated by the board's deliberations, not approved from a staff recommendation. The board, not the staff, decides what to say and where to stop. No matter where the board stops, the CEO is granted authority to use any reasonable interpretation of the board's words. The board can shrink, expand, or change the content of the policy at any time, as long as it does not judge performance retroactively.

This view of organizational issues—as values that can be specified moving methodically from the broadest to more narrow levels—allows the board to manage the amount delegated. The board is always clear about the authority being given away. The recipient of the board's delegation is always clear about the amount of accountability expected in return. There is a continuum of sizes of issues upon which, in Policy Governance, the board owns the broadest level, then successively smaller levels until it decides to delegate, after which it is safe to allow the remaining decisions to be made by others.

It is often observed by other governance authors that the distinction between what is board work and what is executive work is a naïve distinction. There is no universal rule, they contend, to mark where board policy stops and administration begins. Indeed, they are right as far as traditional governance is concerned, for the conventional approach to the board job is unable to make a policy-administration distinction that holds up in the real world. Policy Governance, however, introduces entirely different, more powerful conceptual tools— rigorous "one voice" clarity of delegation using descending levels of board control within the ends/means context. Even though there is still no predetermined or fixed point where board work automatically becomes executive work, each board using the principles we are describing can establish and, when necessary change, a distinct point of delegation applicable to its own organization. It is at that point, by the values of that board, for that organization, for that time, that governance stops and "sub-governance" begins.

To summarize the policy development sequence, Policy Governance boards develop policies which describe their values about Ends, Executive Limitations, Governance Process, and Board-Staff Linkage. Each policy type is developed from the broadest, most inclusive level to more defined levels, continuing into more detail until the board reaches the point at which it can accept any reasonable interpretation of its words from its delegatee. A step-by-step guide to such development of policy documents is available (Carver and Carver, 1997). Ends and Executive Limitations are delegated to the CEO, who is held accountable by the board for accomplishing any reasonable interpretation of the boards expectations in these areas. Governance Process and Board-Staff Linkage policies are delegated to the board Chair, who is given the authority to ensure that the board governs in accordance with its own expectations of itself, using any reasonable interpretation of the policy language.

Board Discipline, Mechanics, and Structure